In the six years since the GDPR became enforceable, many more strong privacy frameworks have emerged around the world and continue to do so at a dizzying pace. Companies who, in that time, have gone through a few cycles of compliance management are better prepared to assess the scope and implication of an avalanche of revamped or new regulations governing non-personal data, cybersecurity, media platforms, data sharing, and evidently, artificial intelligence.

Misconceptions are like old habits; they are great until it is time to switch gears. This article proposes deconstructing fallacies around data, how they come about, why they are maintained, and how they harm compliance, mainly from a European perspective. The sooner these are flushing out of your organization’s thought system and data processes, the sooner staff will achieve a fundamental conceptual alignment conducive to clear communication, effective execution, and on-time delivery.

The Fallacy of Arguing That You Cannot Identify a Person

Not being able to single out a person from given data ensures that GDPR requirements do not apply to your operations. Hence, the inclination is high to argue that data is anonymous and wiggles out of regulatory purview.

The broad GDPR definition of personal data covers any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier or to factors specific to their physical, genetic, economic, cultural, or social identity. In North America, the term Personally Identifiable Information (PII) is actually not far off; but that definition dangerously emphasizes directly identifying information, which further fuels the misconception.

Context is crucial. Name alone, may not lead to identifiability, but combining it with other data points does. Design decision-making on a floating threshold of identifiability is understandably difficult, yet determining whether data is personal or not is not done on a whim by a product owner, a specialist, a legal counsel, or a DPO. In proceedings, courts start by carefully analyzing the nature of the data before examining violations of data protection.

The EU Court of Justice (EUCJ) case law has demonstrated that the ability to identify a person does not need to sit within the organization. A dynamic IP address is personal data if other data points are associated with it but also due to the technical ability to map that address to a customer that sits with the internet service provider.

Non-personal data is either data entirely unrelated to a person, e.g. financial reports, or data that initially was related to many but has since been aggregated, e.g. total payroll expenditure.

At a deep level, qualifying data as personal is a pivotal piece in data governance, but on the surface, it is equally important to ensure that your marketing team aligns with these efforts and does not undermine them by misusing terminology. Medical device manufacturers in the US are known to claim their products’ data processing is anonymous, suggesting their systems are unable to administer the right treatment to the right patient. The term they ought to use in the EU is pseudonymization.

Sometimes misleadingly referred to as pseudo-anonymization, it is one of only a few technical measures recommended by the GDPR. It is intended to reduce the feasibility of re-identifying a person while ensuring systems can still process their data individually. This process is reversible. To further reduce the identifiability of a person, when processing already pseudonymized data inherited from a customer system, make use of data masking APIs that further add a layer of pseudonymization or tokenize the data. Crucially, though irreversible, hashing data does not help claim anonymization since you can map a hash to its input value by hashing inputs and comparing outputs – commonly done in blockchain applications.

Anonymization is not to be confused with de-identification. This confusion is encouraged by the US’ Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) safe harbor method which consists of removing 18 data points from medical records so that data can be shared anonymously, at least from a legal perspective. There is no such pragmatic threshold under the GDPR. In the EU, the aggregation of large enough data sets with few outliers is considered worthy of anonymization. However, this technique may only be good for high-level trends, not so much for detailed statistical analysis or data sharing. In that case, differential privacy or k-anonymity can provide a more scientific and objective approach. Identifiability and anonymization are much-researched topics. Note that deletion of encryption keys, while dramatic, is accepted as equivalent to anonymization, precisely because it is irreversible.

When considering suppliers, keep in mind that misinterpreting data leads to achieving normative compliance on incorrectly qualified assets. Both the GDPR and ISO/IEC 27001 require risk assessments to be performed to determine the security measures to be implemented, but if the data is misqualified to begin with, this inevitably leads to inadequate documentation and controls under both statutory and normative regimes.

Takeaway

If in doubt, treat data as if it were personal. If your employees demand guidance, rely on refreshed document classification so everyone understands what is to be done with personal data when it is stumbled upon outside of normal responsibilities. Then thoroughly supervise the data mapping of your normal activities and own the upkeep of your records of processing. Handling pseudonyms or removing strong identifiers does not make a dataset anonymous. As long as data can technically be traced back to a data subject, it is certainly not anonymous. Claiming otherwise and cutting back on security measures as exfiltration attacks will likely one day prove you wrong.

The Fallacy of Publicly Available Data

With the voluntary digitization of our lives on social media, organizations are often left with the dangerous misconception that if a person has made their data public, it can be used liberally.

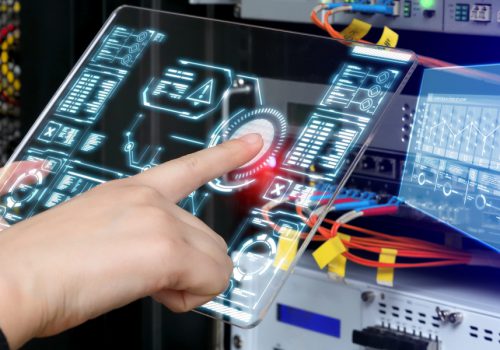

The crux of the problem has to do with lawfulness, or lack thereof. Fundamental to the EU data protection, and going beyond the principle of authority found in the US’ Fair Information Practices Principles (FIPPs), is the triad principle of lawfulness, fairness, and transparency. This triad stipulates that in order to process data, processing must be legitimized by one of six legal bases, lawful; expected to take place and proportionate to the goal pursued, fair; and explicitly communicated before the processing begins, and transparent.

When data is collected from social platforms such as LinkedIn or Telegram, two issues arise, that of lawfulness and that of transparency. Articles 12 and 13 outline how to perform the duty to inform, while Article 14 of the GDPR outlines how that must take place when data subjects have not provided data to you directly. This is what governs publicly available data. This article applies to data brokers or any business that feeds off publicly available information for scouting activities like marketing and recruiting.

Making use of data made public by someone on LinkedIn can be made compliant, provided the data subject is made aware within a month of what data was collected, what the purpose was, and that they can object to it, which leads to the erasure of the data. If your organization has the proper controls to ensure that, then that process is arguably compliant.

AI data scraping is a hot intellectual property and privacy topic, so be on the lookout for more enforcement actions like Clearview AI’s €30,5 million fine last September for building a facial recognition database of Dutch subjects.

Takeaway

Publically available data can be accessed and used, provided the use comes with managed information and data subject rights requirements. From the moment data is processed digitally, or collected in paper form and structured, it triggers the applicability of the GDPR, so make sure that your own data sourcing from marketing data brokers or recruiting agencies is set in a robust process built around transparency, lawfulness, and the exercise of data subject rights. Remember, you are liable for the use of data once you acquire it.

The Fallacy of Corporate Data

Perhaps a helpful mindset to have is to stop considering data as belonging to an organization. EU data protection can only be understood from the ethical vista that data is merely entrusted by the data subject to a data controller for a limited period of time and limited to satisfying its intended purpose. No more, no less.

There is, however, nothing wrong with thinking data generated within the scope of employment is a data asset the organization must protect. However, the interpretation must extend beyond mere security to convey that employees have the same Data Subject Rights (DSRs) and the employer the same obligation as in any data-controller-to-data-subject relationship.

DSRs are fulfilled as a function of the legal base the processing was carried out under. For instance, the right to be forgotten will not apply to data processed under performance of a contract if the employee is still employed. Once they leave the company, the employer may have a legitimate interest in retaining employment data for two years (duration to be determined) to defend itself from legal claims that could be brought against it by its former employee. Fundamentally, what many organizations still fail to recognize is that the above-mentioned activities are distinct, and both require their distinct legal base and communication to the employee. As is true of any form of personal data processing. To date, almost all enforcement cases in Europe have had in common the aggravating factors of weak legal bases, lack of information, and the poor handling of data subject rights.

When using MS365 or Google Workspace, a constant flow of employee data and corporate information is generated. How detailed is your knowledge and documentation of your organization’s activity logs and reports related to authentication, incidents, email payload, project management records, timestamps, and document version history? It remains that your organization is accountable for loss of confidentiality. Believe it or not, the spirit of the GDPR is to provide safeguards against misuses of confidential data.

Consider Kevin, your company’s VP of Engineering using a company car, the location of which is tracked by on-boarded geolocation apps that your insurance company argued needed to be fitted in your fleet vehicles. On his Thursday lunch break, Kevin likes to give his concubine a visit. Kevin’s rival, Bob, VP of Finance, realizes he can use this to coerce Kevin into blackmail and generally make Kevin’s life miserable. Where does employer liability fit in here? Once the blackmail has begun, Kevin places an access request DSR to your DPO, and with that data, easily argues in court that 1) the employee privacy notice did not inform him of such tracking; 2) there was no control to offer them to opt-out, 3) the Finance function was not listed as an internal recipient of this data, and 4) security measures were not implemented to ensure the confidentiality of data which is easily substantiated by the failure to implement appropriate access controls. Kevin’s attorney, Stuart, has little difficulty in claiming damages in countries like Germany and France where the success rate of claims brought against employers is largely favorable to the employee.

Takeaway

Precisely because it is corporate data, your organization has a great responsibility to handle it in a compliant way. Data belonging to employees and product users is merely entrusted to organizations for it to fulfil a string of purposes it must clarify to them diligently. Since personal data should always be kept confidential from those with no need to know, inventory internal recipients with a need-to-know business requirement, and restrict internal access rights to those without. Assume a zero-trust posture and do not assume your own staff will never accidentally or intentionally allow your data to exfiltrate.

The Fallacy of Having Been Provided Consent to Use Data Freely

If a pyramid of misconceptions were to be established, this one would probably be at the apex. Consent to process data is not an open ticket to process data extensively behind closed doors. Each business purpose that the processing fulfills is called a processing activity. Each discrete activity must be lawfully grounded. This is also known as legitimizing the activity and it is done with one of six legal bases. Simplifying further, there are only 4 that you can practically choose from, the choice of which is yours but you will need to opt for the most robust. Typically, consent is the least robust legal base because you cannot force someone to give it or make accessing a service conditional to giving it. More problematic still is that it can be revoked which leads to stopping the processing or deleting the data.

Consider that each purpose needs to have been defined, legitimized, somewhat assessed for risks, and duly documented before it is carried out. Failing legitimization, your organization finds itself unlawfully repurposing data. This happens when data collected and legitimized for one purpose is used to serve one or more additional purposes; e.g. using transactional email addresses to send newsletters. Another condition for consent to be valid is that it be itemized, i.e. purpose-specific. Each discrete business purpose fulfilled by data collected under consent requires its own discrete consent. A third condition to consider is that consent must be informed. Each purpose must be clarified when consent is collected. A mere invitation to “find out how we process your data in our privacy notice” will not do.

For instance, collecting user location for providing better recommendations is one purpose, whereas using it to understand trends in user location is another, and using it to train an AI model is a third purpose. Fundamentally, begin by asking yourself whether consent is best suited to legitimize each of these cases. And by best suited, here is what is meant: consent is not valid in unbalanced relationships like employment and it is technically hard to implement because it comes with six functional front and back-end requirements (three of which were listed above). It should only be used in situations where you can afford to not obtain the data from the user.

Lastly, the provision of consent does not equate the acceptance of terms and conditions. App developers routinely conflate the act of signing up to a service and providing overarching consent for that service’s many uses of data. By now you know the latter is not possible. This confusion is sustained by the deceitful practice of asking users to accept, or worse, consent to the terms of service and the privacy notice.

Note that a notice requires no acceptance whatsoever.

Takeaway

If someone tells you “we’ve got user consent, so we’re covered”, ask them what the consent is provided for. Always start determining the purpose(s) for processing; and if consent is the chosen legitimization, determine each purpose to be consented to. If you rely on an overarching acceptance of terms of use or if consent is implied from passively using a feature, this is not consent and your product needs an urgent review.

The Fallacy of Paying for Data

While a contract may be binding on two organizations doing business with one another, it does not transfer compliance nor rights of use to another party. A data processing agreement between two parties does not confer onto the second party the lawfulness of the processing carried out by the 1st party. Each organization that has an interest or business purpose for using the data is -or becomes- a data controller. By now you know that each purpose must be legitimized, so each controller is responsible for the lawfulness and transparency that comes with processing data for their own purposes.

While a compliant data broker will have collected consent from the data subject for being added to a database, the purchaser of the list, however, will have obtained no such consent from the data subject to being contacted for marketing purposes. Crudely simplified, this is the unresolvable compliance issue with ad-tech and real-time bidding that targets, tracks, and exploits users with a flurry of technologies.

When you engage, as I do, with data brokers advertising trade show contact lists of professionals in your industry, you may notice they make use of fake names, disposable email addresses, and work for legit-sounding-yet-fictitious organizations in the US. They conceal their organization’s identity because they sense much could go wrong, but most disturbingly, they have no clue what is at risk.

Takeaway

Beware of trusting a marketing colleague arguing they have paid for data. Dismiss the data broker telling you “we are GDPR compliant”. Worry about your own compliance, and whether your handling of personal data is lawful from the moment you acquire the data. Article 14 of the GDPR is where you should look to understand what to provide individuals who have not directly given you their data and do not be shy, give the full details of your broker (Art. 14.2.f).

The Dangerous Primacy of Product User Data

When establishing a privacy program, I often hear that the organization would rather focus on their product and leave out their internal processes. As a consultant, I am happy to oblige, but as a DPO, I cannot be instructed on how I carry out my duties. Organizations often need reminding that their own employees are first and foremost data subjects that also provide sensitive information. They also tend to instinctively blot out the fact that sales, marketing, webforms, cookies, payroll, finance, development procurement, recruiting, employment, workplace medicine, leave management, learning, and health and safety, all generate large amounts of data.

In practice, however, by keeping internal processes in the remit of privacy, organizations are effectively encouraging their own staff to understand related policies and have privacy at the top of their mind when performing daily tasks. When training employees, relating the content to misuse of employee data drives the point across on security and compliance more effectively than referring to abstract use cases.

Undeniably, privacy engineering and compliance management do come at a cost. Recruiting experts externally or upskilling them internally requires careful budgeting. Regularly engaging staff and rolling out GRC projects also takes a toll on product roadmaps and delivery calendars. Understandably so, many organizations relying on external DPOs wish to reduce the time that the office spends on internal process data.

Unless you rely on an external low-cost template-driven DPO-as-a-Service solution, your DPO will likely remind you that 1) they have statutory compliance monitoring tasks they need to fulfil by virtue of the position they hold, and 2) they cannot be directed on how they conduct their tasks; their professional integrity depends on it.

Takeaway

Employees are people too. Exemplify to your staff how you want customer data to be treated by extending data governance to their own data. Communicate about it regularly in numerous channels and sources, or design your own qualitative, needs-based data protection training.

The Fallacy of Automating Compliance

There are typically two ways to handle compliance. You either try to automate and rely on templates to get as much done as you can, or you sit down and get your hands dirty with the intention to own the requirements, tasks, and output. From a budgetary perspective, the former option is the most enticing. It gives a sense of getting most of the work done pre-baked by the experts sourcing you the toolbox: tick boxes are reassuring and lend themselves well to reporting.

But what if you wanted to determine what it is your company is actually getting from it? Would your KPIs and templates truly help ascertain whether staff understand what they have been doing and why they have been doing it? Ask yourself what the risks are of pushing out questionnaires to already overworked staff. Will they provide any answer to get past those pesky mandatory fields keeping them from moving on to the next task? Will they make the logical connections between data and decisions that are not necessarily already hard-wired in your platform? Is your organization’s compliance posture in any way better than it was six months ago? Have sales and procurement teams become any more autonomous in their ability to clarify what your product does or what they need your suppliers to provide? If you are somewhat familiar with normative compliance and external audits, you will agree that the last mile details of whether or not staff understand a requirement is often where auditors get you.

Platforms are great for structure but relying on them blindly leads to the wrong people being assigned roles and responsibilities, it hinders the clarification of processes and relations that are key to memorization, engagement, and a sense of achievement. The privacy notice of an organization that has blindly chosen to rely on platform-issued questionnaires and left out qualitative reviews typically reads ”we retain your data for our legitimate purpose…for as long as it serves our purpose”. Thus, miserably failing its ethical and statutory duty to inform about the actual purposes and legitimate interests pursued.

If you lack resources, take it slow. Unless your data has been breached or you have noticed a concerning increase in DSRs, there is no reason for your organization to rush through compliance. In practice, much like acquiring a security certification that is not legally required, GDPR compliance is something many companies still carry out to sign a new contract. Determine what documents and product functionalities these customers want to see first. When data mapping, leave no stone unturned and keep track of the compliance gaps that you think require more than 12 months to close. Do not minimize in any way the depth of your inventories or their accuracy. If you automate anything, keep a human in the loop, ensuring this human knows what they are doing.

Takeaway

If you are being pitched a compliance management solution with “our platform allows you to send awesome questionnaires to your staff” ; ask yourself what lack-of-ownership risks this tool introduces and what dynamic DPO and project manager duo has been assigned to own your compliance.

Conclusion

Use the following questions to informally assess the degree of alignment that exists between your business, product, analysts, architects, and developers on matters of data protection and governance. Invite your DPO or legal counsel to the call to sit quietly and take notes. What they hear should shape their compliance roadmap and save you years of inefficiencies.

- Do our security risk assessments only focus on the impact to security and our ISMS or do they also acknowledge the possible impact of breaches on data subjects?

- Do we anonymize data? How do we explain it internally and to the world?

- Do we know precisely which data processing activities we perform based on consent and legitimate interest? Do we fully control the opt-in and opt-out related to these two?

- Is any processing relying on user consent actually necessary?

- Do we call our privacy notice a privacy policy? Do we know why?

- Have we purchased data from a broker? Do we fully own the underlying data protection requirements?